Eosinophilic Fasciitis: Evidence for Treatment and Response

The characteristic skin and fascial hardening is a later sign of disease.

The classic hallmarks of Eosinophilic fasciitis (EF)—orange peel textured skin, the “groove sign,” hard depressed areas of skin known as “induration”—that are more readily recognized by physicians and may make diagnosis easier, tend to follow other, more general, symptoms. To learn more about Eosinophilic fasciitis, you can find its Diagnosis Description here. Those non-specific symptoms include non-pitting (if you press on the swollen area, it doesn’t stay depressed) swelling, particularly of the arms and legs, redness and possibly pain. Fever and fatigue may also be present. Biopsy of the deep tissue will show swelling and a collection of out of place white blood cells, including eosinophils. Once the hardening and thickening of the deep tissue occurs (time lapse unspecified in any of the research I’ve found), the out of place white blood cells (called inflammatory infiltrate) tend to no longer be present, or are present in very small numbers. That’s why on biopsy examples of Eosinophilic fasciitis, there may be just one Eosinophil, and a handful of lymphocytes, identified. In the most recent comprehensive review article the authors report that it’s actually the process of Eosinophils breaking down in the tissues that leads to the classic signs of disease

After the degranulation of eosinophils in the fascia…proteins are released and accumulated…with toxic and fibrotic potential.

(Mazilu et. al, 2023)

During later stages of disease, inflammatory infiltrate in the deep tissues may actually be undetectable, while circulating white blood cell counts, and non-specific inflammatory markers, are still above normal. What this all amounts to is a difficult clinical picture to diagnose early, but not surprisingly, it is early diagnosis and treatment that leads to the best outcomes.

(Mazilu et. al, 2023)

Research Limitations

First, a caveat to all the research I am about to review: it is not scientifically rigorous. The findings summarized here exemplify the difficulty in researching an orphan autoimmune disease with no validated classification criteria, and likely very little, if any, research funding. I wrote about Orphan Autoimmunity here. Mazilu et. al sum it up succinctly in their review article:

The therapeutic approach in EF is currently unclear; there are also no randomized studies regarding therapy in EF. (2023)

But there is a limited body of research that physician scientists out there have published on drug treatment options.

I’d just like to briefly address non-drug treatment options, which I think are fascinating, woefully under-studied, and potentially very beneficial to autoimmune sufferers. I have been on the sidelines for biofeedback sessions and naturopathic remedies that, in some cases, have addressed an underlying cause and markedly improved symptoms. But, when I focus on individual autoimmune diseases that get very little research devoted to them from the get-go, it’s often hard to find studies on non-pharmacological therapies in named autoimmune disease. So far—I fully own it—this newsletter definitely reflects the drug-based myopathy of the medical model of care. I do not present pharmacological research because I think they are the only worthwhile options. I present them because that is the research that is overwhelmingly conducted on autoimmune disease treatment options.

Drug Treatment Options

Prednisone

Mazilu et. al (2023) report a two participant case series who were both treated with weight-based Prednisone dosed at 1 mg/kg per day with an unspecified taper schedule. They report “rapid resolution” of blood levels of eosinophils and “normalization” of Estimated sedimentation rate (ESR) values. But softening of the skin took weeks to months. I was surprised that improvement in skin symptoms was a possibility, and within a relatively short time frame. They cite UptoDate, a clinical treatment tool that in their citation addresses eosinophilic conditions as a whole to identify a Prednisone treatment limit of 1.5 mg/kg/day for three months, and if that is unsuccessful, it should be followed by a different treatment option.

Mertens et. al (2017) review treatment in 17 participants with severe morphea (non-specific to Eosinophilic fasciitis), 0.5-1 mg/kg/day for 5-70 months. A rapid response was reported, but six participants (35%) experienced relapse after steroids were stopped. They review another study where the dose was 0.3-1 mg/kg/day for 3-39 months, with a relapse rate of 45% when steroids were stopped. For this reason, Mertens et. al do not recommend treatment with corticosteroids alone.

Lebaux et. al (2012) conducted a chart review study on 34 participants with Eosinophilic fasciitis. Results for 32 participants are reported, since 2 were lost to follow up. All 32 received prednisone as a first-line therapy for a range of 6-115 months. “Twenty-two (69%) patients had complete remission, six (19%) patients had remission with disability and four (12%) patients had failure with persistent active disease. Complete remission was achieved in 17 (94%) of the 18 patients who received steroids alone…”

Methotrexate

Mazilu et. al (2023) suggest Methotrexate at a dose of 15-25 mg per week, with a duration between four and six months without evidentiary review for its use.

Mertens et. al (2017) consider methotrexate as “an effective treatment for morphea” based on their review of the studies up until their 2017 publication date.

Prednisone and Methylprednisolone Pulses (MPP)

Lebaux et. al (2012) conducted a chart review study on 34 participants with Eosinophilic fasciitis. Results for 32 participants are reported, since 2 were lost to follow up. “Fifteen (47%) patients received MPPs at treatment initiation. Compared with patients who did not, patients who received MPPs less frequently received an ISD {Immunosuppressive drug, almost always methotrexate in this study} (20 vs 65%, P = 0.02) and were more likely to have complete remission (87 vs 53%, P = 0.06)…The use of MPPs was associated with a better outcome and allowed a significant decrease of the risk of requiring of an ISD treatment as a second-line therapy.”

Prednisone and Methotrexate

Lebaux et. al (2012) conducted a chart review study on 34 participants with Eosinophilic fasciitis. Results for 32 participants are reported, since 2 were lost to follow up. Concurrent morphea-like lesions were associated with this combination of treatment, as was the lack of initial treatment with methylprednisolone pulses. Methotrexate was used when initial treatment was unsuccessful.

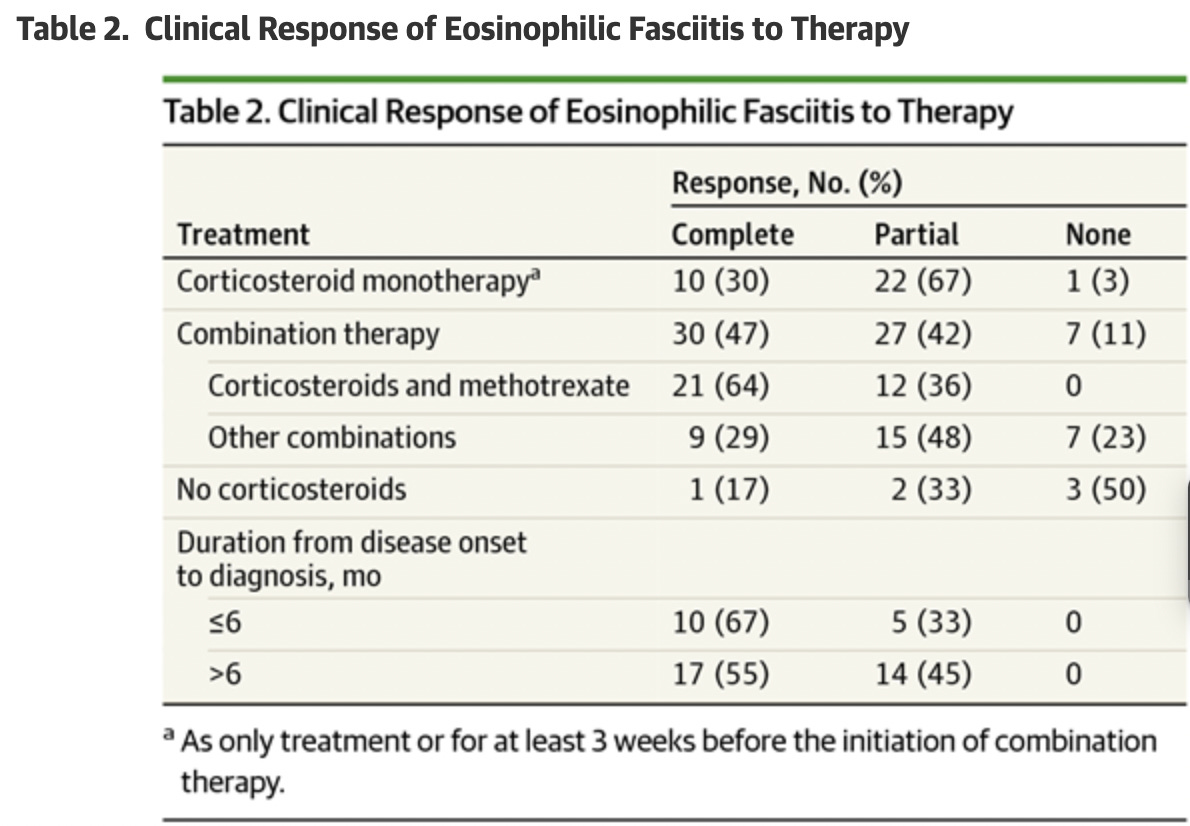

Wright et. al (2016) studied 63 participants with Eosinophilic fasciitis. 33 of those participants received a steroid and methotrexate as initial therapy. “During a mean (SD) follow-up of 39 (43) months, complete response was more likely with the combination of corticosteroids and methotrexate (21 of 33 patients [64%])”

Tull et. al (2018) studied 10 participants with Eosinophilic fasciitis. 6 of the 10 participants received dual prednisone and methotrexate therapy. 4 participants achieved complete remission. The remaining two achieved partial remission. The other four participants received varied treatment combinations that make it difficult to draw general conclusions.

Important takeaways from the Wright et. al study (63 Participants)

Mean (SD) time from onset of EF to diagnosis was 11 (8) months. Seventy-nine percent of patients (37 of 47) were initially misdiagnosed, most frequently with systemic sclerosis (SSc), deep vein thrombosis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, or cellulitis. Most patients who were misdiagnosed with SSc underwent unnecessary evaluation for internal disease and failed to receive corticosteroids before the correct diagnosis. Four patients who were misdiagnosed with hypereosinophilic syndrome or eosinophilic leukemia underwent bone marrow biopsies and 1 patient received chemotherapy.

…The most common misdiagnosis was SSc, likely because both EF and SSc frequently present with induration of the extremities. Distinguishing these 2 conditions is imperative because corticosteroids are first-line therapy for EF, whereas corticosteroids are generally avoided in patients with SSc, given a potential association with renal crisis.

…This study’s limitations include its retrospective nature, the possibility of spontaneous resolution rather than therapeutic effect, and the fact that initial therapeutic intervention occurred at various disease stages, thereby complicating assessment of clinical response. Despite the small sample size, this study represents the largest cohort to date of patients with EF. Further investigation is needed to determine an appropriate treatment algorithm for patients with EF.

(Wright et. al, 2016)

(Wright et. al, 2016)

Mufti et. al (2022) Try to Quantify Treatment Results of Case Studies & Case Series

The authors search two databases and find 21 studies that include 34 patients and 38 biologic treatments. Biologic treatments were not used as a the only treatment. They found that biologic treatments were used with steroids 28.9% of the time, immunosuppressants 26.3% of the time, and a combination of all three 26.3% of the time. Please keep in mind that these percentages are being applied to a very small number of overall patients, so although they’re a useful conceptualization tool, how meaningful these findings are is questionable. Biologic treatments included:

Interleukin-6 inhibitors were used in 10.5% of treatments used, or 4 out of 38 treatments in 34 patients. Interleukin-6 had the greatest frequency of cases with improvement: 1 out of 4 cases had complete resolution within 3 months, and 3 out of 4 cases had partial resolution within 5.8 months. With only four patients studied, it’s hard to generalize these results without further research.

tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitors were used in 34.2% of treatments used, or 13 out of 38 treatments in 34 patients. “TNF-α inhibitors had the second greatest frequency of improvement:” 3 out of 13 cases had complete resolution within 6.3 months, partial resolution in 7 out of 13 cases within 6.9 months, and no resolution in 3 out of 13 cases.

immunoglobulins were used in 31.6% of treatments used or 12 out of 38 treatment in 34 patients. Complete resolution was achieved in 4 out of 12 cases within 25.3 months; partial resolution in 4 out of 12 cases within 10.8 months and no resolution in 4 out of 12 cases.

anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies were used in 15.8% of treatments used or 6 out of 38 treatments in 34 patients. Complete resolution was achieved in 2 out of 6 cases within 8.0 months; partial resolution in 2 out of 6 cases within 0.8 months; and no resolution in 2 out of 6 cases.

tyrosine kinase inhibitors were used in 5.3% of treatments used, or 2 out of 38 treatments in 34 patients. Too few cases to further characterize.

combination therapy (thrombopoietin mimetic agent with immunoglobulins) were used in 2.6% or treatments, or 1 out of 38 treatments in 34 patients. Too few cases to further characterize.

In reviewing the limitations of this study, the authors note that because biologic therapies accompanied other medications, it’s impossible to determine which medication was responsible for improvement. However, in 23 of 31 patients, the non-biologic medications used were started before the biologics and did not result in therapeutic response, which led to starting the biologic therapy in addition to the prior medication. It argues for the efficacy of the addition of the biologic treatment.

(Mufti et. al, 2022)

There’s One Chinese Study Noting Chinese Medicine

Treatment regimens were evaluated in 78 patients; however, only 35 patients had been followed up at the time of writing. Only 16 patients received corticosteroids (with an initial dose of 30 mg/d prednisone equivalent), whereas all the patients received Chinese herbs called fusong or fusu tablets. The patients were followed up for an average period of 20 months (range: 3–60 months). We prescribed patients who had rapid progression of the disease oral corticosteroids and patients who had relatively stable disease with Chinese herbal medicine. After treatment, eosinophil counts were reduced in all patients. Remission with disability occurred in 31 patients (89%), and treatment failure occurred in four patients (11%). Remission was achieved all four patients who received steroids and Chinese herbs and in 31 of the 35 patients who received Chinese herbs. Patients with treatment failure tended to have a longer diagnosis time delay (8 years vs. 15 years) and symptoms located in distal limbs.

This study is interesting for its high remission rate and sparing use of steroids. I know nothing about Chinese herbs, and their uses, and specifically the ones listed here. I also found a different study in Chinese of 45 participants, which also acutely reminded me of my knowledge, access and language limitations.

Delayed Diagnosis Associated with Incomplete Treatment Response

In a retrospective chart review study of 89 participants with Eosinophilic fasciitis, a complete response rate to various treatments was 60% at 3 years. The longer the delay in diagnosis, the more likely the treatments tried would fail and

No single immunosuppressant agent was associated with a superior response during treatment.

(Mango et. al, 2020)

Why It Matters

Broadly, in autoimmune disease writ large, diagnostic delays matter to disease course. Unchecked autoimmunity can cause irreversible damage. For Eosinophilic fasciitis particularly, the non-specific nature of initial symptoms (swelling, redness, pain) presents a major diagnostic challenge. It is encouraging, though, that even after later signs of disease, tissue changes are reversible, with a number of different treatment options—some with promising documentation of a relatively high percentage of participants with complete resolution of symptoms, compared to other autoimmune disease outcomes.

This concludes my look at Eosinophilic fasciitis. Next week, I’ll turn my attention to the overarching umbrella over Eosinophilic fasciitis: Scleroderma. Thank you so much for reading. For those who are new to AutoimmuneDx, I am currently writing posts based on reader-requests for more information and analysis on particular autoimmune diagnoses. If you would like me to take a closer look at a particular diagnosis, please leave a comment below. If you don’t feel comfortable commenting publicly, email me at autoimmunedx@gmail.com. If you would like me to clarify a post, a concept, a word, or anything in-between, please don’t hesitate to leave a comment or send an email.

References

Lebeaux D, Francès C, Barete S, Wechsler B, Dubourg O, Renoux J, Maisonobe T, Benveniste O, Gatfossé M, Bourgeois P, Amoura Z, Cacoub P, Piette JC, Sène D. Eosinophilic fasciitis (Shulman disease): new insights into the therapeutic management from a series of 34 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012 Mar;51(3):557-61. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker366. Epub 2011 Nov 25. PMID: 22120602.

Mango RL, Bugdayli K, Crowson CS, Drage LA, Wetter DA, Lehman JS, Peters MS, Davis MD, Chowdhary VR. Baseline characteristics and long-term outcomes of eosinophilic fasciitis in 89 patients seen at a single center over 20 years. Int J Rheum Dis. 2020 Feb;23(2):233-239. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13770. Epub 2019 Dec 6. PMID: 31811710.

Mazilu D, Boltașiu Tătaru LA, Mardale DA, Bijă MS, Ismail S, Zanfir V, Negoi F, Balanescu AR. Eosinophilic Fasciitis: Current and Remaining Challenges. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan 19;24(3):1982. doi: 10.3390/ijms24031982. PMID: 36768300; PMCID: PMC9916848.

Mertens JS, Seyger MMB, Thurlings RM, Radstake TRDJ, de Jong EMGJ. Morphea and Eosinophilic Fasciitis: An Update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017 Aug;18(4):491-512. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0269-x. PMID: 28303481; PMCID: PMC5506513.

Mufti A, Kashetsky N, Abduelmula A, Lytvyn Y, Sachdeva M, Yeung J. Biologic treatment outcomes in refractory eosinophilic fasciitis: A systematic review of published reports. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022 Apr;86(4):951-953. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.089. Epub 2021 Apr 2. PMID: 33812957.

Tull R, Hoover WD 3rd, De Luca JF, Huang WW, Jorizzo JL. Eosinophilic fasciitis: a case series with an emphasis on therapy and induction of remission. Drugs Context. 2018 Oct 2;7:212529. doi: 10.7573/dic.212529. PMID: 30302114; PMCID: PMC6172017.

Wright NA, Mazori DR, Patel M, Merola JF, Femia AN, Vleugels RA. Epidemiology and Treatment of Eosinophilic Fasciitis: An Analysis of 63 Patients From 3 Tertiary Care Centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(1):97–99. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3648